The Long Walk charmingly blends science fiction with deeply rooted Laotian spiritual beliefs, creating a film that is both haunting and thought-provoking. I watched The Long Walk at a time when its themes resonated deeply with my own life—when I had just lost two uncles. One from my paternal side and one from my maternal side within a day, both to cancer. In the past decade, I’ve experienced the loss of six family members, beginning with my mother. This film, with its haunting exploration of longing and letting go, offered a poignant reflection on these experiences through the lens of Theravada Buddhism.

“What the heck is Theravada Buddhism?”—You might ask.

It’s the oldest form of Buddhism, predominant in Southeast Asia, including Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. It is often overshadowed by the more widely recognized Mahayana and Tantra practices in the Western world. Yet, its teachings on the impermanence of life, the nature of suffering, the cease of suffering, and the complexity of human minds and relationships are profoundly depicted in Mattie Do’s narrative.

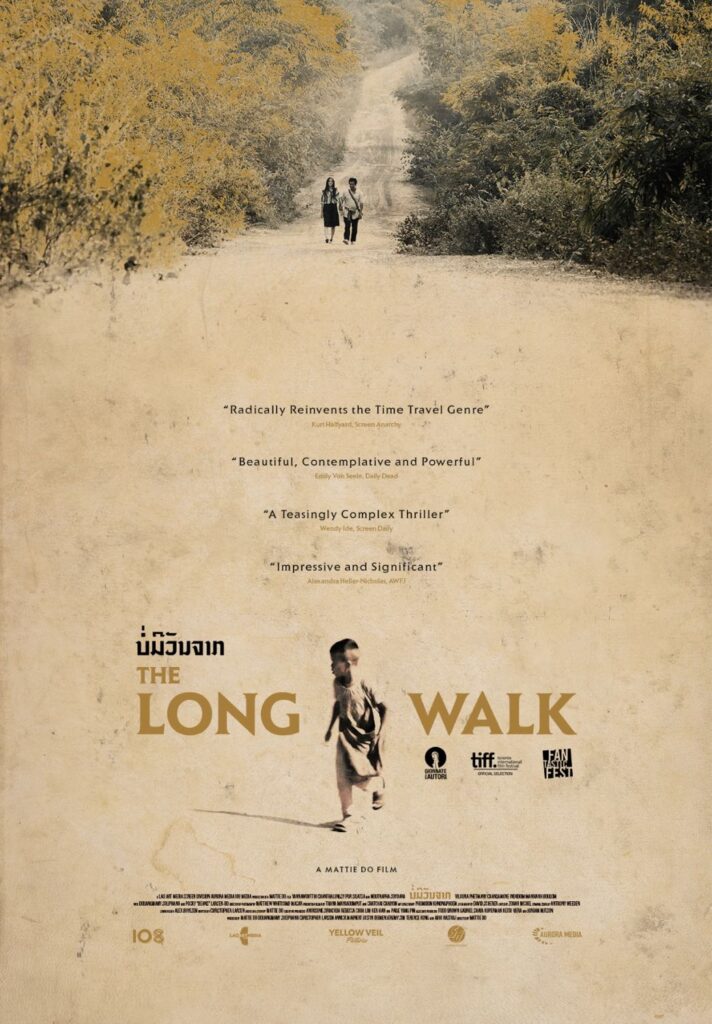

Mattie Do, a Laotian-American filmmaker, trained as a ballerina before becoming Laos’s first and only female film director, known for her work in horror cinema. Born and raised in America after her family emigrated during the Laotian Civil War (1959-1975), Do’s journey from ballet to filmmaking is as unique as her cinematic style. She maintains her distinctive charm and style through the emotional nuances in her films, not unlike the improvisation of a dancer during a performance. Her three films – Chanthaly(2012), Dearest Sister(2016), and The Long Walk(2019) – all feature ghosts.

Do often employs speculative fiction to explore the cultural authenticity of the Lower Mekong Basin region, using horror elements to examine the lives of people in Laos.

Her position as a diasporic filmmaker allows her to bridge Laotian cultural narratives with broader speculative fiction genres. This approach is particularly notable because it’s a relatively new genre in Laotian cinema, which she uses to explore complex themes of spirituality, gender, and cultural identity. Through her films, Do examines the intersections of tradition, contemporary life, and the future in Laos, creating narratives that resonate both locally and globally. This is especially evident in “The Long Walk,” which has become an inspiring work both nationally and internationally.

“The Long Walk” tells the story of an old man living in a future remote Laotian village who discovers he can traverse time, aided by the ghost of a woman he encountered half a century earlier. The film brings us back to a pivotal moment in the protagonist’s life: when he was a boy, he stumbled upon a fatally injured woman in the bush with an overturned motorcycle. He stayed with her until she took her last breath, then befriended her ghost. This encounter marks the beginning of a lifelong attachment, leading the old man to begin his quest to travel through time, attempting to alter the past and make the present better.

However, as the film unfolds, it becomes clear that the protagonist is not merely a well-intentioned figure. He is a serial killer, engaging in acts of mercy killing suffering women without their consent. His actions are not just about misguided compassion but are deeply rooted in toxic masculinity. The film critiques male savior complexes, showing how these can lead to further harm rather than genuine help. He believes he is helping those in need, forcefully imposing his twisted sense of compassion on others. His actions reveal a deep-seated violence inherited from his father—a loser who acted irresponsibly and failed to provide a stable and nurturing environment for his family. The protagonist’s actions are also driven by a desire to change the events leading to his mother’s death.

This exploration of the protagonist’s gendered identity adds another layer of complexity to the narrative, positioning him as both a victim and perpetrator of patriarchal violence.

The protagonist’s delusion is further highlighted by his practice of collecting the finger bones of those he has killed, which reflects his severe attachment issues. This act echoes the story of Aṅgulimāla, a figure from Buddhist scripture who collected his victims’ fingers to prove his prowess. Aṅgulimāla was eventually redeemed by the Dharma of Buddha, becoming an Arahant and transcending Saṃsāra. This is a significant event in Buddhist history, often seen as a symbol of the Buddha’s compassion and the possibility of transformation. However, unlike Aṅgulimāla, the protagonist in The Long Walk remains trapped in his mirage, convinced that he is leading his victims’ spirits to true peace. His graveyard garden, filled with spirit houses and the remains of those he has “liberated,” becomes a macabre reflection of his misbelief that he is a Messiah, not unlike a twisted version of the Western concept of utopia.

The presence of the ghostly figure in the film underscores the spiritual beliefs that have long existed in the Lower Mekong Basin—a region that includes Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand. This area is a significant part of the Indosphere, a cultural and religious territory deeply influenced by Indian civilization. However, it’s important to note that the Lower Mekong Basin’s religious and cultural practices are not just a product of Indian influence but also a result of a complex history of local development, trade, and exchange with other cultures, including China, other parts of Southeast Asia, and Europe. Here, cultural practices represent a unique blend of Indigenous beliefs, such as the worship of spirits, ancestors, and Theravada Buddhism, which were introduced through trade and interaction with India, later influenced by the Khmer Empire, and further developed through connections with Sri Lanka.

Spirit houses, small shrines embodying local animism, exemplify the fusion of indigenous beliefs with Buddhism in the Lower Mekong Basin. These structures, predating Buddhism’s arrival, house and honor local spirits. Rather than replacing animistic practices, Buddhism blended with them, creating a syncretic spirituality. This integration demonstrates how the region’s beliefs adapted to new religious ideas while preserving traditional elements, reflecting the complex cultural tapestry until today.

“In Theravada Buddhism, which is a significant influence in Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand, the concept of karma plays a central role.

Karma refers to the law of cause and effect, where one’s actions in this life or previous lives determine the circumstances of future existence. The old man’s journey in The Long Walk is a poignant reflection of this principle. His actions, though seemingly altruistic, are ultimately self-serving; they stem from his inability to let go of his own pain and guilt over his mother’s death when he was young. The metaphorical use of time travel to explore the concept of karma and its consequences is a core tenet of Theravada Buddhism: suffering (dukkha) is an inherent part of life, and trying to manipulate outcomes with bad karma can often lead to more suffering. His desire to change the past is not truly about helping others but about alleviating his own suffering, which only leads to more complications, locking himself in a thousand loops of suffering across countless rebirths, still attached to the pain of his failed family.

This film is not merely a ghost story but an exploration of the complexities of suffering, letting go, and the consequences of one’s actions.

By using ghosts as a time machine, Mattie Do’s clever storytelling presents a profound work about accepting reality and the death of loved ones when it comes, while also telling us not to cling to what has already passed.

The Long Walk thus becomes more than just a sci-fi narrative. It is a meditation on the human condition through the lens of Laotian spirituality, Buddhist philosophy, and gender dynamics. The film’s blending of genres—sci-fi, horror, and spiritual drama—allows it to explore the complexities of karma, guilt, patriarchal violence, and the cycle of life and death in a way that is both culturally specific to Laos and universally resonant for audiences worldwide.

Mattie Do’s The Long Walk offers a unique cinematic experience deeply rooted in the influence of Indian civilization on Southeast Asia, as reflected through Theravada Buddhism. The film employs supernatural elements not merely for entertainment but to probe profound insights into the human psyche, the innate desire to alter the past, and the repercussions of such attempts. It also delves into family violence, revealing the deep emotional scars it leaves on the protagonist.

The film is a potent reminder that our actions, even when well-intentioned, may often stem more from our ego and personal pain than from a genuine desire to help others. True peace of mind comes from accepting reality and understanding nature, rather than attempting to control what lies beyond our grasp. Yet, despite these lessons, it’s not easy to let go—just last night, I still dreamed of making merit for my mother, even though it’s been ten years since my beloved passed away.

This essay is a part of the “Mek◊ng Sci-Fi” series by Vorakorn “Billy” Ruetaivanichkul. It is published in English billyvorr.com and Thai TheMissionTH.co and was completed as part of the 2024 ArtsEquator Fellowship. The views expressed are solely those of the author. Connect with him on Facebook, IG, X, or Discord.